Home > About Mood Cow

About Mood Cow

Vision — Proactive medicine for mental health

Mood Cow envisions proactive medicine by bridging prevention (public health) and treatment (clinical practice). Mood Cow was created for everyone, especially with our future generations in mind, aiming to help them acquire life skills backed up by scientific evidence to take care of their most important asset, the brain. To do so, Mood Cow first formalizes the foundation of mental health, then derives practical solutions from it.

Problem — Lack of formalization in preventive mental health

These days, it is common to hear infamous statistics by the National Institute of Mental Health: one in five Americans need mental health treatment (Link to source). The implication is simple—everyone needs preventive mental care, but finding the right solution that works for everyone is not so simple, if possible at all.

Just like skin care and dental care, a simple routine should be able to help manage stressful events and situations before things get worse. But everyone is different. Everyone has different values, faces different challenges, and is immersed in different environment. And most importantly, everyone feels and reacts differently to stressors because of their genetic makeup, neural development and adaptation, biochemical balance, environmental exposure and circumstances, and in some cases, biological disorder.

Mental states are invisible and difficult to measure objectively. The subjective nature of individual mental health data and the variability within target populations pose major obstacles for scientific studies to generate reproducible outcomes to be applied as guidelines for public health and clinical practice.

The corollary is that there is no universal preventive measure that works for everyone today. Therefore, instead of inventing and promoting a particular preventive method, it seems reasonable and valuable to build a formalized framework with principles to help people find their own preventive routines that work for them. This is the idea behind Mood Cow.

Background — Current state of mental healthcare

To understand the context behind Mood Cow's effort, it helps to understand the current state of mental health care from a rather critical viewpoint. It begins with a tragic story about a man who once suffered from anxiety and insomnia.

- A man was stressed at work. He feared he might lose his job. He had no history of mental health problems, but lately he felt anxious and couldn't sleep well. One day, he decided to ask his primary care doctor for help. The doctor prescribed a medication for anxiety and another medication for insomnia. The drugs didn't help. He returned to see the doctor three times in a few weeks. At each visit, the medication dose was increased. Two weeks after the last doctor visit, the man shot and killed himself.

Suicide rates are increasing worldwide. [1] In theory, suicide occurs when stressors exceed one's coping abilities. In reality, it is sometimes insufficient or inappropriate support or treatment that could push individuals to undesirable behavior.

Medication is currently the first choice in the treatment of mental illness. For example, a government study [2] shows that one in ten Americans take antidepressant medication. Antidepressants are the third most commonly prescribed drug for Americans of all ages. The most disturbing statistics is that 80% of those antidepressants were prescribed by non-psychiatrists without any accompanying psychiatric diagnosis. [3]

Unfortunately, the efficacy of psychiatric treatment recently became questionable. In November 2014, an independent research organization Cochrane published a concerning report on the efficacy of medication and psychotherapies for treating depression in children and adolescents [4]. The report concluded: "On the basis of the available evidence, we do not know whether psychological therapy, antidepressant medication or a combination of the two is most effective to treat depressive disorders in children and adolescents."

In June 2015, T. R. Insel, then the director of the National Institute of Mental Health, warned that "four decades of drug development resulting in over 20 antipsychotics and over 30 antidepressants have not demonstrably reduced the morbidity or mortality of mental disorders." [5]

To make things worse, the quality of psychology research also became questionable. According to an analysis by Open Science Collaboration published in August 2015, two-thirds of published psychology experiments failed reproducibility tests [6]. In other words, scientific claims made by these psychology studies may not be reliable.

In the meantime, there is a crisis going on at the front line of clinical care—the emergency room. The National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors reported a survey of more than 6,000 emergency departments nationwide. 70% reported boarding psychiatric patients for hours or days, and 10% boarded patients for several weeks. [7] The American College of Emergency Physicians points out the problem: "Limited funding, limited resources, and patient placement difficulties have cumulated to the current crisis of mental health patients boarding in the emergency department." [8]

Academic view of mental health intervention

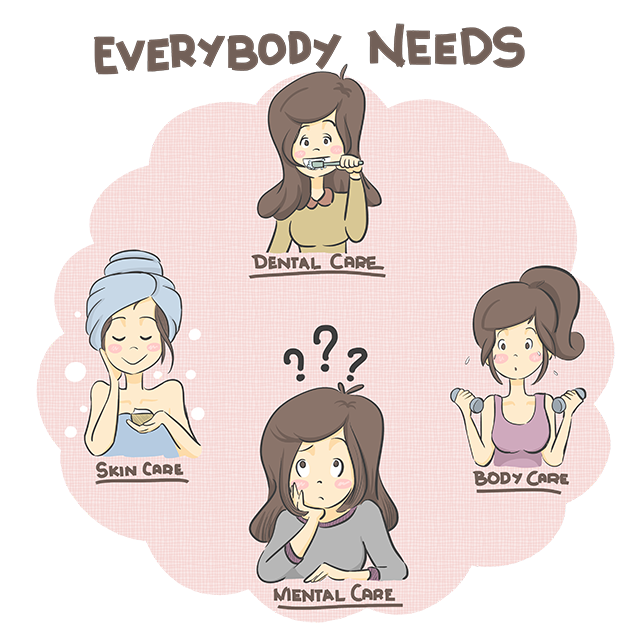

The World Health Organization (WHO) released a report in 2004, promoting the concept of evidence-based prevention and promotion in mental health [9]. In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (now National Academy of Medicine) published a report, presenting the idea of preventive mental health for young people [10]. In 2010, WHO released a comprehensive action plan for mental health [11]. Wahlbeck [12] proposes a broad approach to mental health by promoting both positive well-being and prevention.

(Institute of Medicine 2009)

These grand visions are rooted in a population-based public health model. A public health approach "encompasses a focus on epidemiological surveillance, health promotion, disease prevention, and access to service," according to the Surgeon General's report on mental health [13]. Considering the breadth of topics to be negotiated, including education, economics, government policies, social service, parenting, and partnerships with health-care systems, the public health approach is overwhelmingly ambitious and long-term in its return on investment. For that reason, Weissman [14] for example argues that we need to combine public health models with clinical practice for patients with early signs of disorder within primary care.

How does prevention work? According to WHO [9], "preventive interventions work by focusing on reducing risk factors and enhancing protective factors associated with mental ill-health."

Unfortunately, the academic work on preventive interventions do not offer practical solutions. Currently there is no standard structure to capture and represent risk and protective factors. There is no quantitative measurement tool. Time-consuming psychiatric evaluations are the only way to identify specific risk factors for individuals today, and such evaluation only takes place when the patient is already suffering from severe symptoms.

Mood Cow is the first to address this problem.

Engineering view of mental health intervention

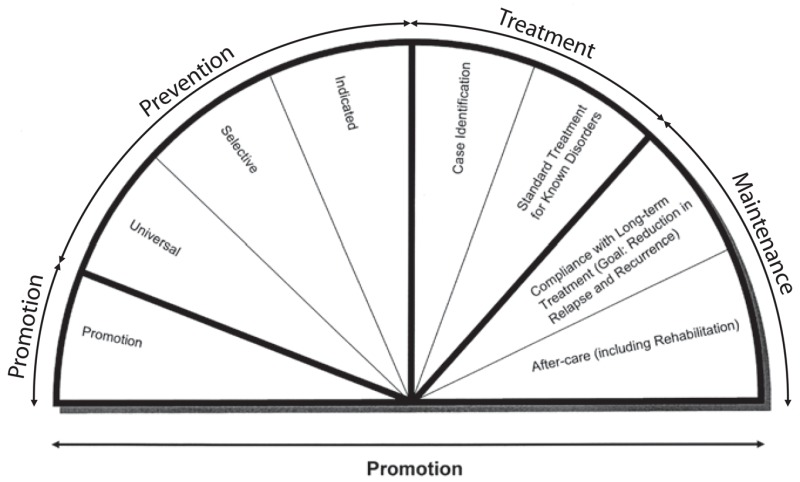

Let us step back and see a bigger picture of mental health from a practical point of view. Let us think of health as a maintenance process from cradle to grave. There are two types of maintenance: preventive and corrective.

Preventive maintenance is a process of taking actions to eliminate or minimize future corrective actions. Changing oil for your car or brushing teeth is an example of preventive maintenance.

Corrective maintenance is a process of taking actions to repair functional failure. Replacing engine parts or filling a tooth cavity is an example of corrective maintenance.

Prevention is not about treating or monitoring symptoms. Treating or monitoring symptoms is irrelevant when your car is running smoothly or your teeth are feeling fine without any indication of symptoms. The goal of universal prevention is to identify potential root causes and taking actions to reduce their effect. Contaminated lubricant in your engine or sugar in your mouth is an example of root causes for potential failure in the future. That's why you periodically change oil or brush teeth.

By the time you see smoke coming from your car or you feel pain in your tooth, it becomes a matter of time before the problem gets worse. In engineering, this is called a P-F interval, the amount of time elapses between the detection of a potential failure and its deterioration to functional failure. The goal of indicated prevention is to maximize the P-F interval to avoid functional failure as long as possible.

In mental health, the word "treatment" typically refers to corrective actions. The way healthcare systems work today is when a symptom affects your life quality, you reach out to a healthcare provider to receive appropriate treatment to address the symptom. Psychiatric medications and psychotherapies are corrective actions to treat symptoms. This is reactive. How can we make it more proactive so that we can reduce the need for treatment?

The answer is about awareness of root causes. Not all root causes can be identified or eliminated, especially in mental health where individual circumstances are complex and vary greatly. But what if there is a system that helps us become aware of general influencers that may relate to potential root causes?

Mood Cow is the first to offer a practical solution to this problem.

Mood Cow — Think different

Today, one in five American adults experiences a mental health issue in a year, and one in five youth aged 13 to 18 experiences a severe mental disorder at some point during his or her life. [15] The global cost of mental health is projected to exceed $6 trillion in 2030—larger than the cost of cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases combined. [16]

We clearly have a lot to overcome in mental healthcare, AKA "an orphan of healthcare." However, this is an opportunity to bring new ideas by thinking differently and broadly. Mood Cow is just that.

Contact and share Mood Cow

Please contact info@moodcow.com for questions and comments.

References

- [1] Suicide Statistics. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Link

- [2] Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant use in persons aged 12 and over: United States, 2005–2008. NCHS data brief. National Center for Health Statistics. 2011. Link

- [3] Mojtabai R. Olfson M. Proportion Of Antidepressants Prescribed Without A Psychiatric Diagnosis Is Growing. Health Affairs. 2011;30(8):1434-1442. Link

- [4] Cox GR, Callahan P, Churchill R, Hunot V, Merry SN, Parker AG, Hetrick SE. Psychological therapies versus antidepressant medication, alone and in combination for depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD008324. Link

- [5] Insel TR. The NIMH experimental medicine initiative. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):151-153. Link

- [6] Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716. Link

- [7] Glover RW. Miller JE, Sadowski SR. Proceedings on the state budget crisis and the behavioral health treatment gap: The impact on public substance abuse and mental health systems. NASMHPD. 2012. Link

- [8] American College of Emergency Physicians. Practical Solutions to Boarding of Psychiatric Patients in the Emergency Department. October 2015. Link

- [9] World Health Organization. Prevention of Mental Disorders: Effective Interventions and Policy Options. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. Link

- [10] National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions; O'Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE, editors. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009. Link

- [11] World Health Organization. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013-2020. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. Link

- [12] Wahlbeck K. Public mental health: the time is ripe for translation of evidence into practice. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):36-42. Link

- [13] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General, Rockville,, MD. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health. 1999. Link

- [14] Weissman MM. Applied public mental health: bridging the gap between evidence and clinical practice. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):45-47. Link

- [15] Mental Health By the Numbers. National Alliance on Mental Illness. 2015. Link

- [16] Bloom DE. Cafiero ET. et al. The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum. 2011. Link